In Filaments of Possibilities

In this article, art historian and New York City correspondent Osvaldo Martinez Abreu investigates the legacy of Ruth Asawa's six decades of work. Featuring over 300, the Museum of Modern Art's "Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective" spans across the fields of experimentation Asawa pursued in finding endless possibilities and potentials in art creation . "Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective" is now on view at the Museum of Modern Art, through February 7, 2026.

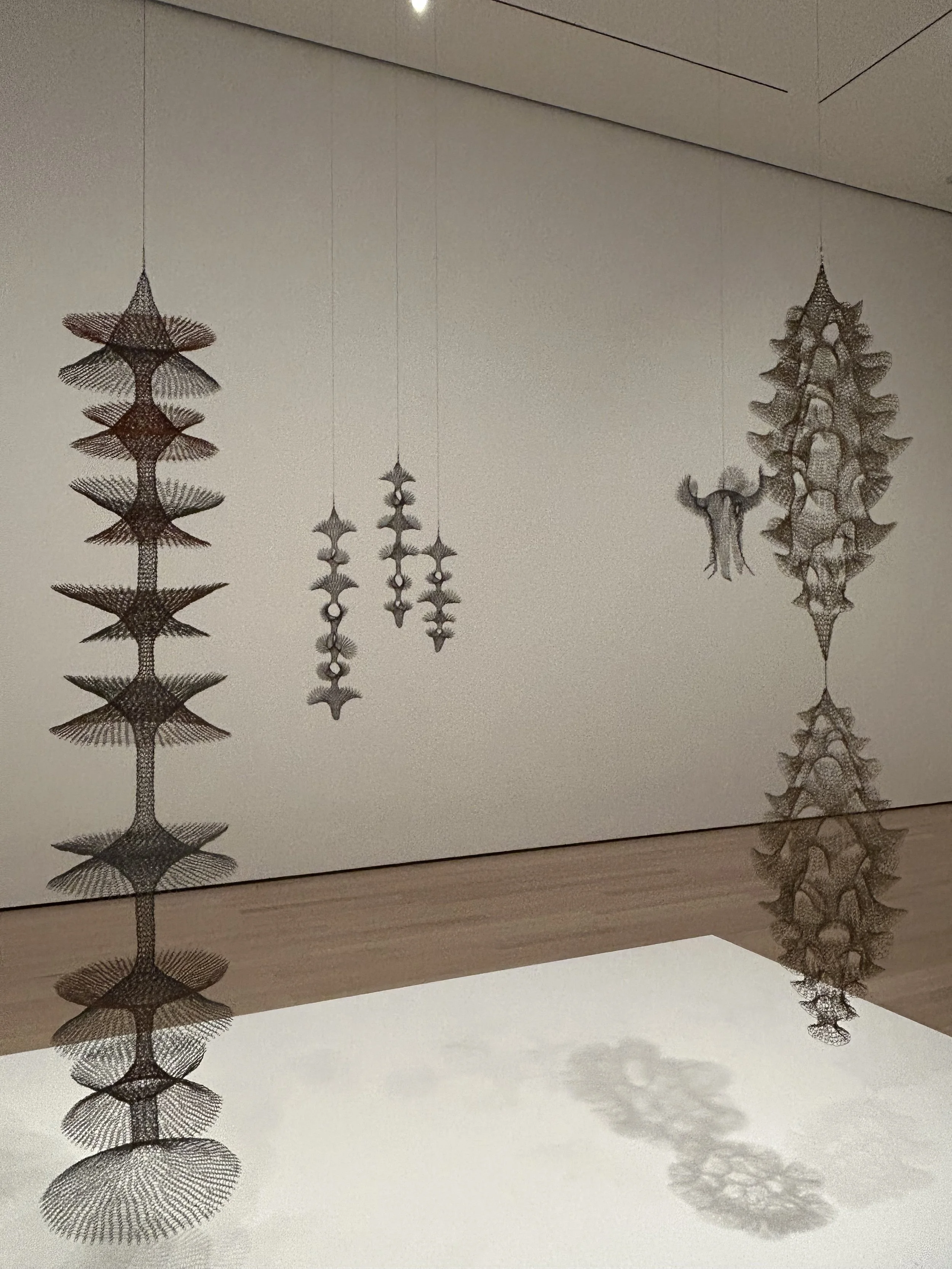

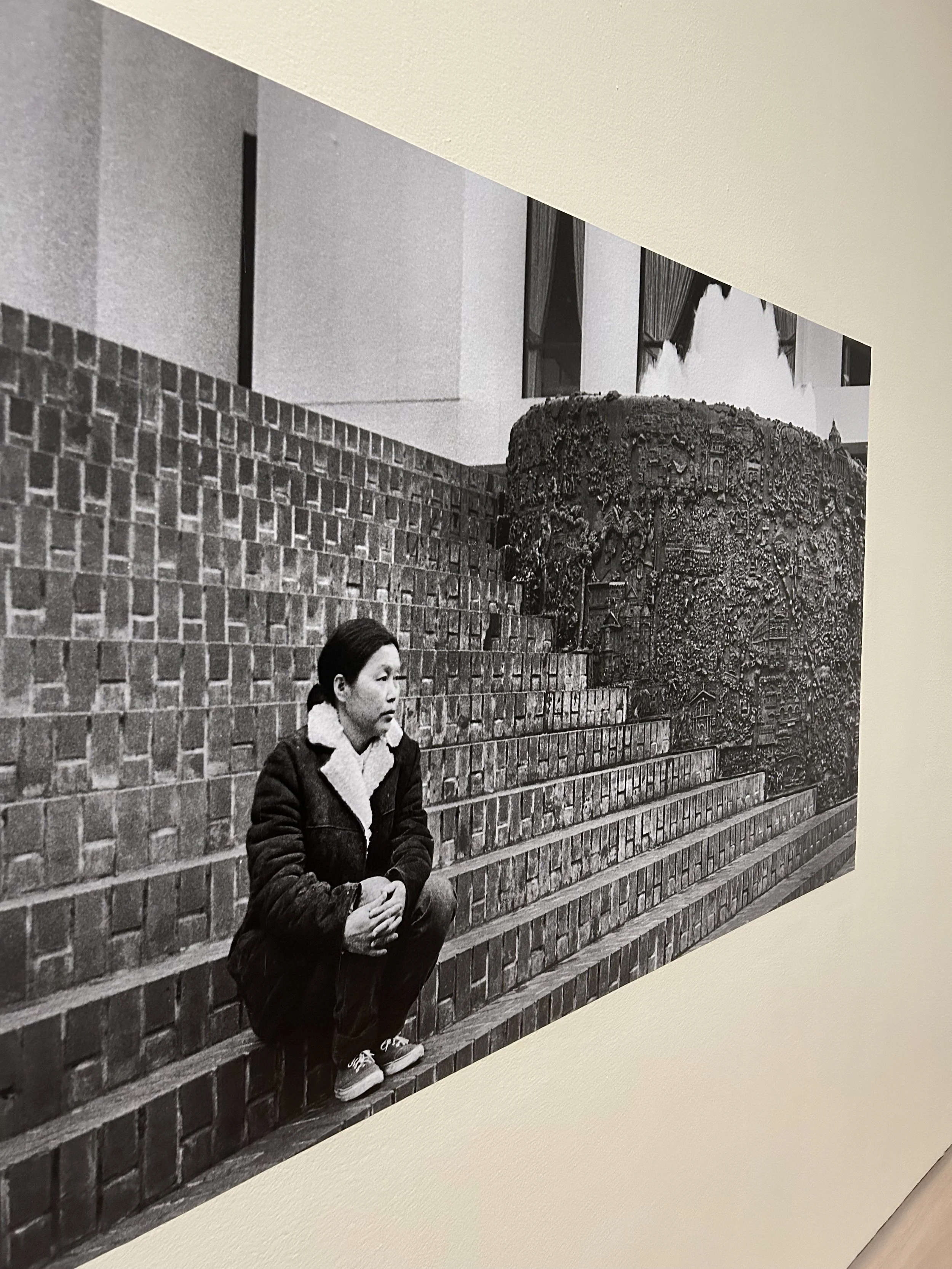

Installation View: Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective, The Museum of Modern Art

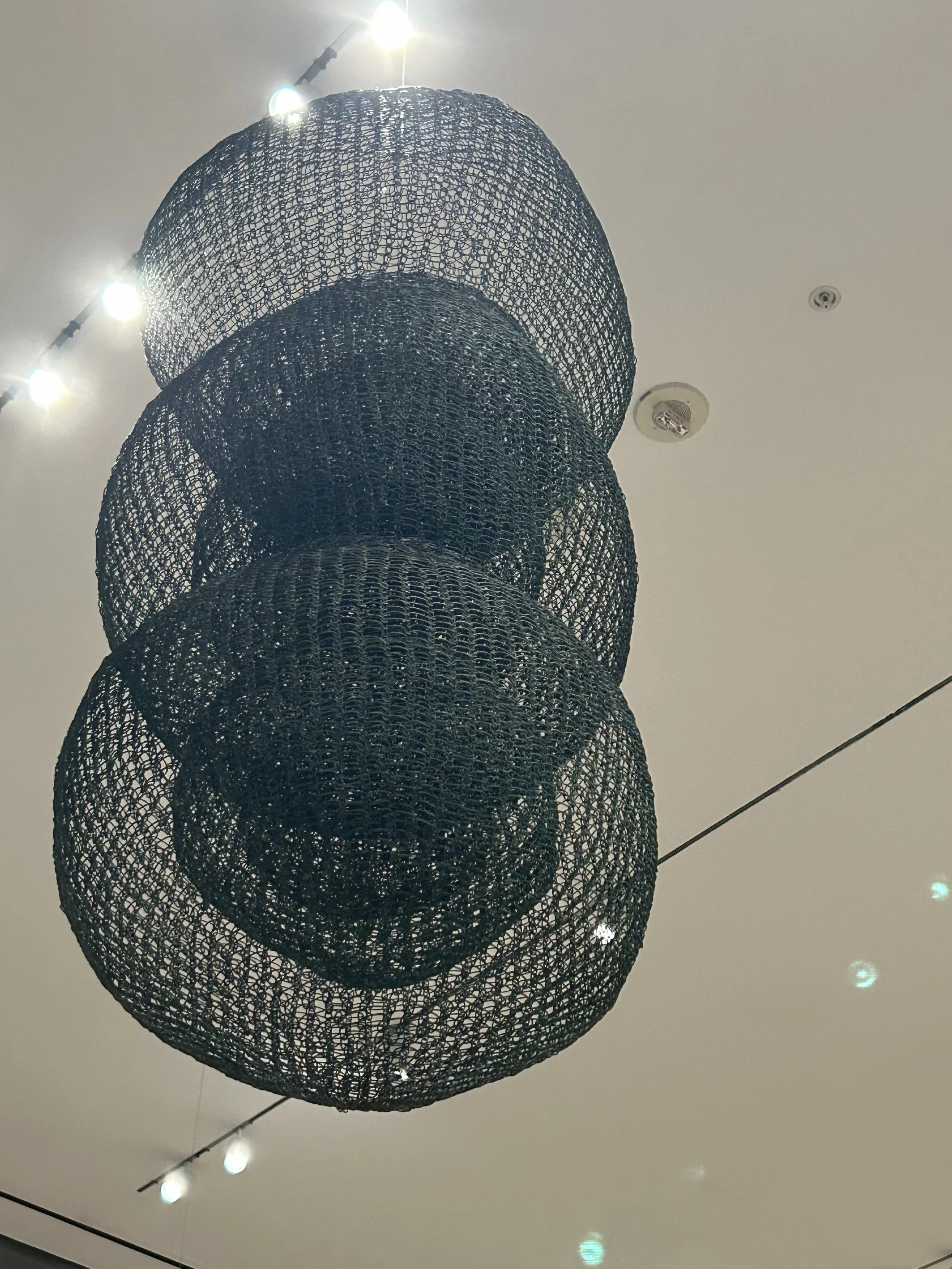

In woven webbings of detailed history, Ruth Asawa’s (American, 1926 -2013) Retrospective, for the Museum of Modern Art, interlaces six decades of the artist’s career in exploring the boundaries of form and material. Across 300 works, the artist showcases the means of questioning and transformation through mediums including wire sculptures, bronze casts, drawings, paintings, prints, and public works. In invocations of the everyday around her, Asawa detailed forums of contemplation. None had a singular means, but instead there was a multitude in the world around. In the way it was rendered by the artist, even in the way it was looked upon by viewers, through constant shifting of their stance. Asawa was fueled by evincing possibilities.

Organic lines, formations of patterns, lacings of overlapping shapes and forms, adorned the work that Asawa created every day, since her studies at the Black Mountain College, in the late 1940s. With material as mundane as paper and wiring, Asawa crafted in constant experimentation of old materials and techniques into new possibilities. Her interdisciplinary methods, from lopped-wired sculptures to ink-based drawings, viewed the possibilities in material culture and what they represented. In her abstracting reality, there was a refining of what is visible. Asawa crafted not just in means of documenting, but her work was a means of finding new ways of seeing the everyday world around her.

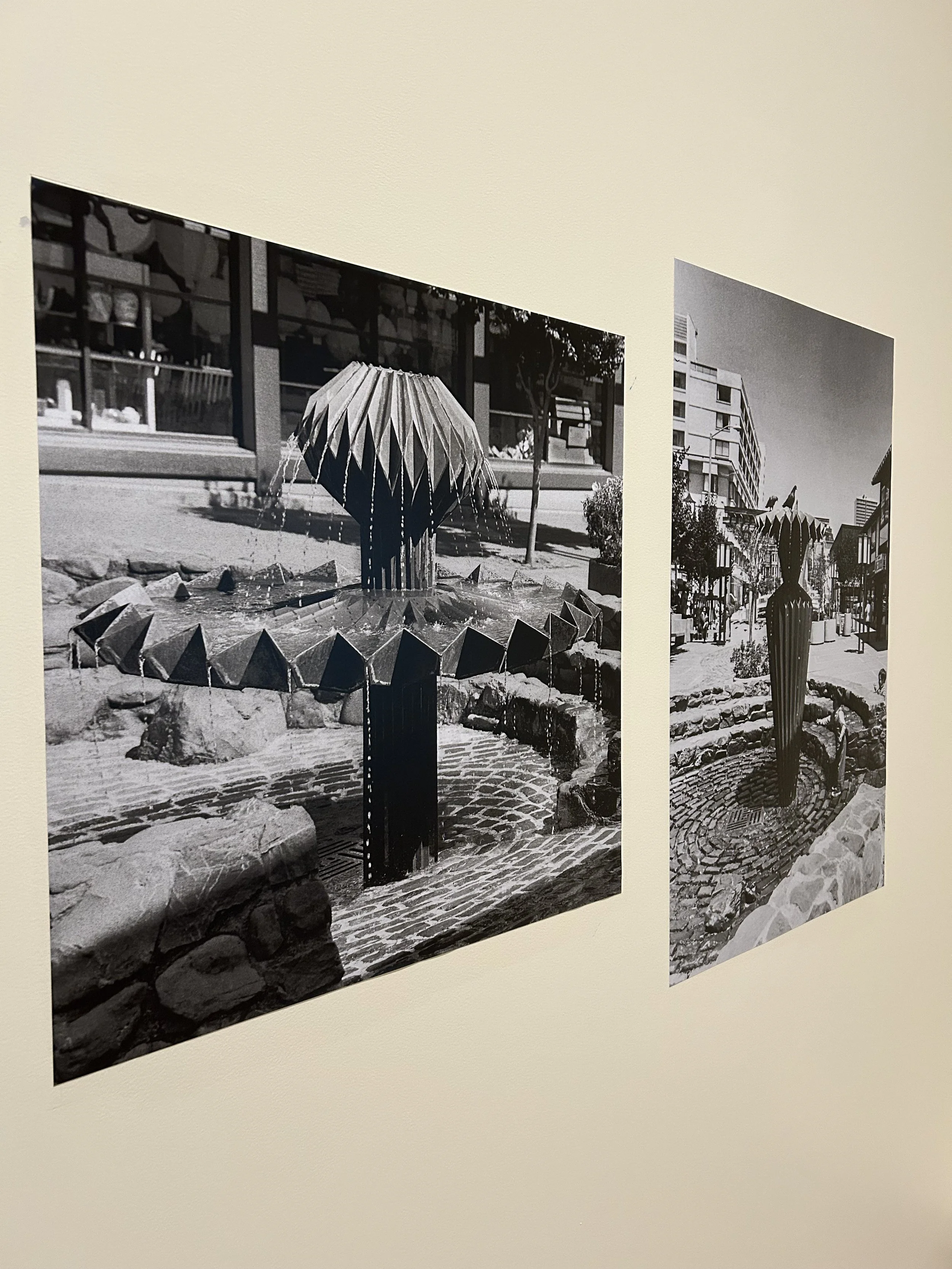

As her famed sculptures visually appear, Asawa forms interconnected laces of memories and possibilities found in the world around. Beyond her sculptures and paintings, Asawa’s public work of fountains, murals, and monuments form a crucial part of Asawa's artistic principles, that of community and integration of art upon the very day. The two are not separate entities, but as Asawa created every day, they form filaments that interweave to generate forms, representing what it means to make art of the everyday. This retrospective, the first posthumous survey of the artist, details not just a catalog of the artist’s work, but integrates the viewers in asking what it means to ‘see’ the world around.

Asawa varied her way of seeing nature and the materials that it gifts. In close observations, she was in constant experimentation with materials, but also with the possibilities of forms, lines, and space within art. In shifting these individual distinctions into new elements of what is possible, Asawa’s work invites us to observe the individual remnants and how they interact with their surrounding form and the composition as a whole. It is not about observing from afar and seeing a singular form, but Asawa’s work is to be contemplated up close, seeing how the individual parts come to form the observable whole. We are, as Asawa’s art is, formed from the many. This practice of observable parts becomes the basis of the artist’s artistic practice and view of the world. As she states, “[h]ow one sees, one does. How one does, one is.”

![Untitled (BMC.116, Abstraction [Dogwood Leaves]) c.1948-49 Watercolor, paint, colored pencil, and graphite on paper mounted on paper and paperboard Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of Josef Albers](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64d6902d80f0e7535c37a81a/1765847821325-YAJJ1OWR8TO5T4MXO2NV/IMG_2743.jpeg)

Alongside experimentation, Asawa’s work comes from questioning and observing. After her immigrant family was detained during WWII’s policies targeting Japanese communities, she began her art making within the internment camps. She drew from life around her and of the other detainees, incarcerated under Executive Order 9066. Supervised sketching trips to the surrounding areas of Rohwer, Arkansas, built the foundational drawing lessons, alongside other classes from previous detainments. Alongside observations from nature, formal teachings from previous working artists, including three from Disney Studios, helped build the preliminary means of her art practice. And as she would go on to state, “[i]t was the art instruction by professional artists that kept our hopes alive.”

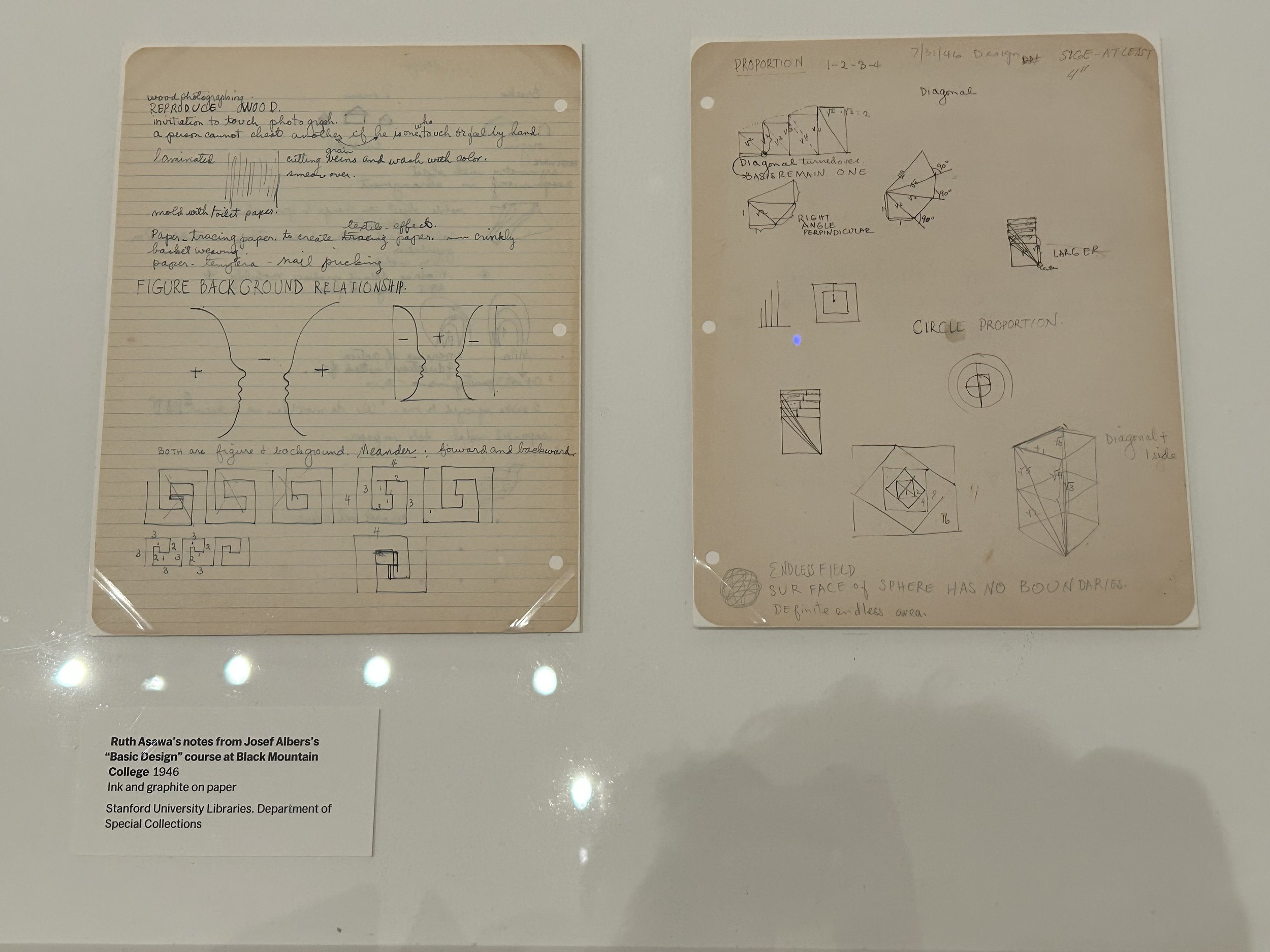

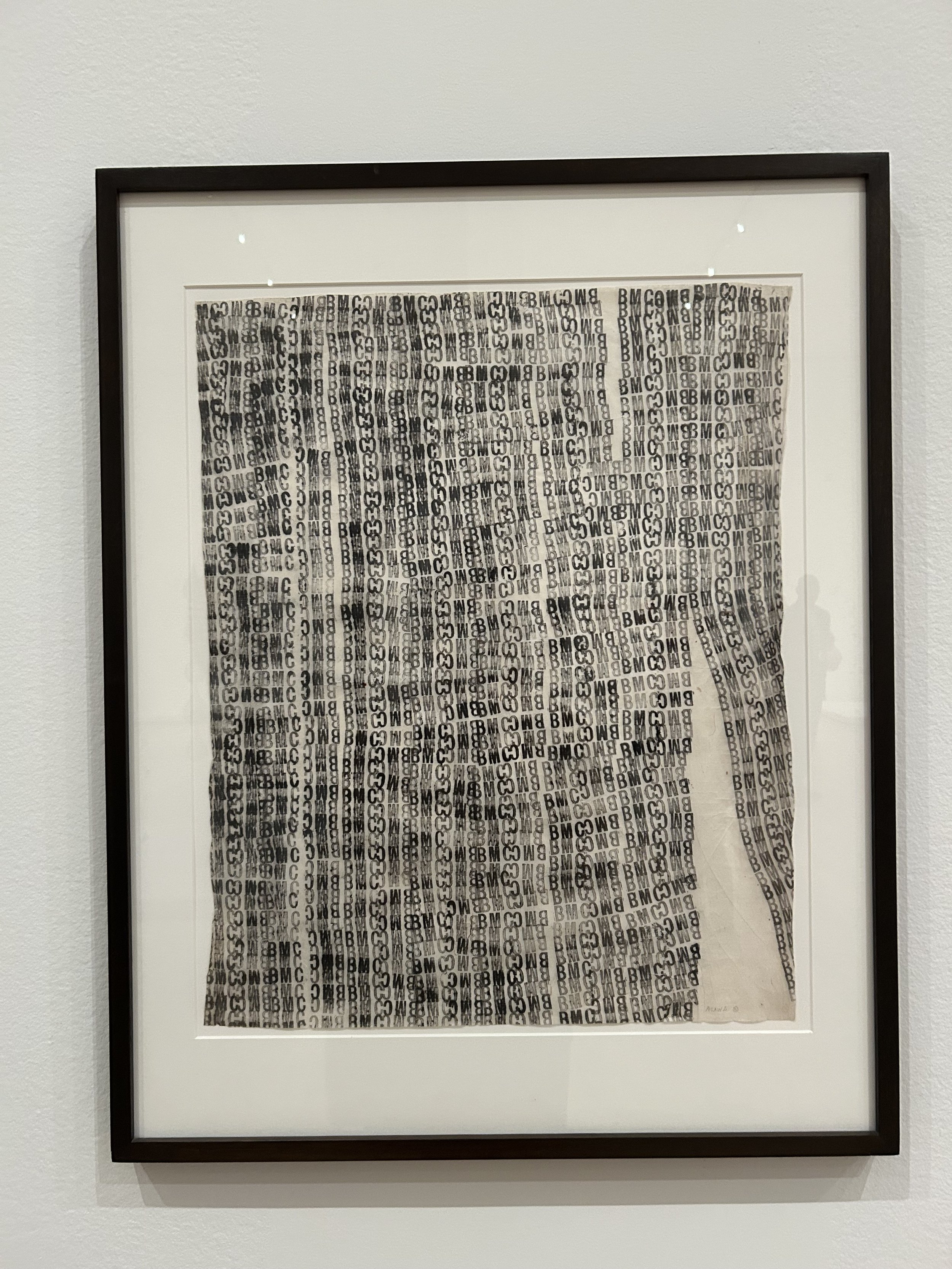

With her academic training in 1946, after being denied an art teaching degree, the North Carolina school of Black Mountain College became the center from which she started experimenting with the reaches of the material culture around her. Upon reaching the school, the twenty-year-old artist had three years of college education and two exhibitions under her name. There, her education under mathematician Max Dehn, architect R. Buckminster Fuller, and former Bauhaus instructor, Josef Albers, had her trained in observing how material and textile can be observed and manipulated into new possible forms. In constant exercises, such as drawing the Greek meander motif in a singular continuous line, Asawa formed her later mantra of developing the role of ground and figure.

These times would forge her foundational artistic practice of constant experimenting. This was seen not only in three-dimensional sculpting, but also in her process of using lettered stamps. Asawa worked them by altering their direction and position, layering them next to and on top of each other, forming new visual forms beyond the singular letter. But the material and techniques that Asawa used were not just those in her immediate vicinity. During a trip in 1947, Asawa, having volunteered as an art teacher in New Mexico, found herself unraveling the possibilities of wire-based baskets used by vendors as egg carriers. She followed the traditional techniques of the locals and then returned to unravel what she was taught, pushing the possibilities of the wire through new loops and reversing how the strands meshed together, shaping a new sculptural form.

From an artistic mantra to a spoken motto, Asawa’s move, in 1949, to San Francisco, would go on to help build the ongoing tandems that would illustrate her career. In building her famous looped-wire sculptures, Asawa formed a crucial ideology that would span throughout her career, “[e]verything is connected, continuous.” Her line work was to become a sequence of uninterrupted space. Building onto another, individual vessels formed a whole. In this webbing of pieces, Asawa details continuity as a crucial element in her art making, but also how the world is to be.

To her, there is an interconnected form that renders what is seen from the outside and from the inside. Through this, we are guided to understand how our innermost beings form not just from outside forces, but also from our own perspectives, looking inward. Her three-dimensional sculptural forms are constantly affected by movement. They are shifting kaleidoscopes of shapes and forms, crafting new perspectives, altering the canvas displayed through cast shadows. In this, we can see Asawa’s teaching; just as easily as we observe the world, it can change and we change with it. With these shifts comes a new forged perspective of what is.

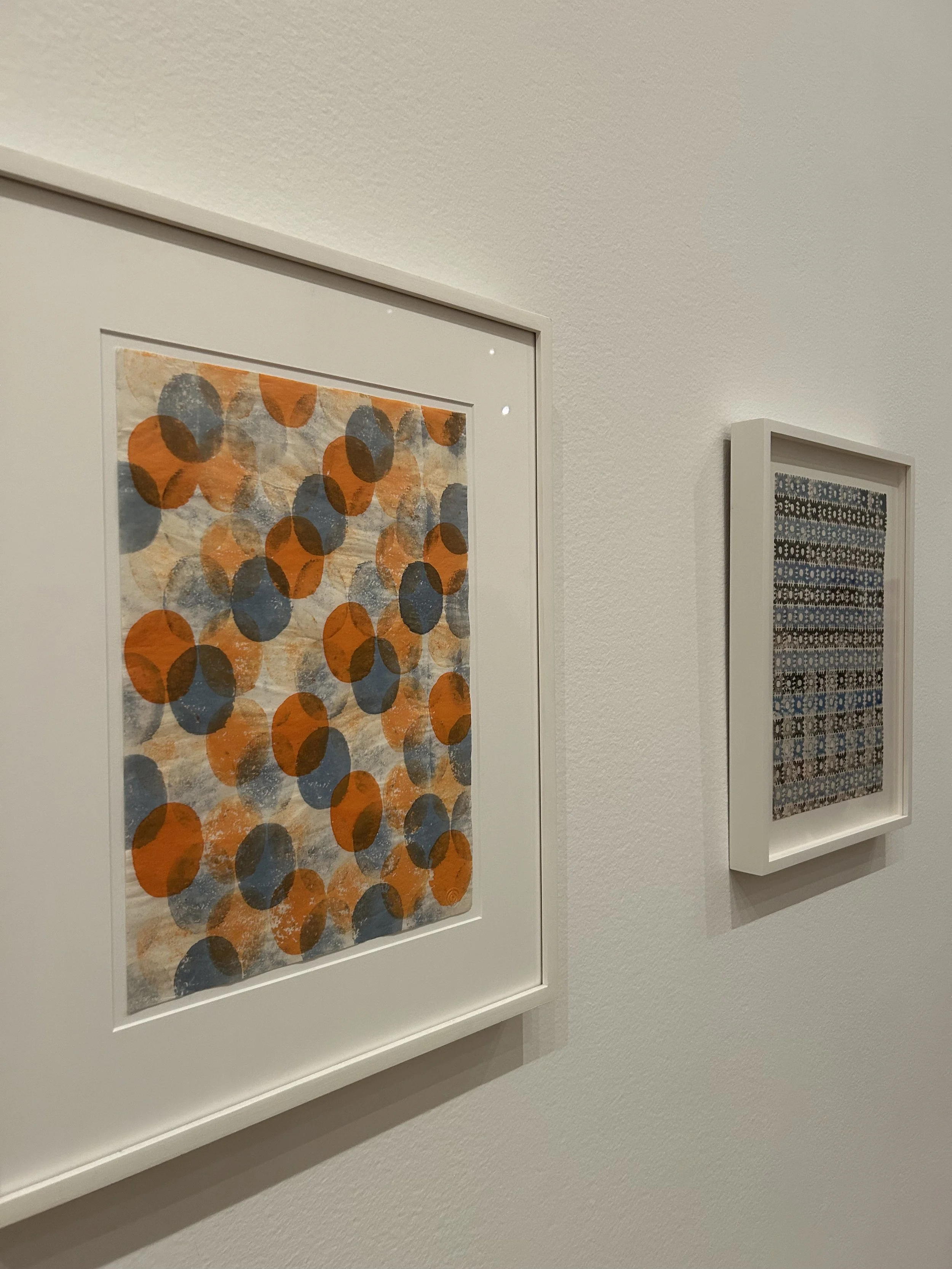

Much of the everyday life that inspired Asawa’s transfiguration of varying materials came from the natural world around her. The imprints of nature echo through the repetition of shape and patterns. Within her wire-sculpture forms, held as if by air, to her drawings on paper, viewers are witness to the eternal and ever-growing connections of nature and their reliance on one another. This abstraction of nature and reality forges a refining of what is visible in front of us. As in her work of Dogwood Leaves, during her time at Black Mountain, outlines curve in all forms resembling the leaves that bound the college. These colors are layered in overlapping patterns, giving a glimpse of transparency in their wake. In this, Asawa layers her experimentation with inspirations from her adjacent world and its natural features.

“Nature was a teacher, according to Asawa. Constant and close observation of nature becomes an instrumental factor for the artist. Not only were the materials that nature gave tools, but discerning their shapes and forms, and how they constantly transform, formed essential factors of Asawa’s method of creating.”

Its geometric shapes and structures were abstracted and composed into varying possibilities. Once again, we are informed of the multitude that forges all around. It was this composed abstraction that led to the iconic wire sculptures that have become synonymous with Asawa. While inspired by dried desert plants and by basket forms of sculpting that she worked with during her days at the Black Mountain College, Asawa began to experiment with sculpting in layered wires. These bundles were to branch out into interconnected networks. Singular lines became shapes and geometric patterns of varying qualities. These shapes were layered, nested, interlocked, and warped in cascading mosaics of negative space and figured lines. Whether it was in three-dimensional forms or in two-dimensional drawings, space in both was an area of constant change.

Through varying gestures, line and form, upon negative space, were bounded by endless possibilities for Asawa. Through Asawa’s technique, simple lines, multiplied upon themselves in varying degrees and forms, redefined the space around it. This never stopped within a singular form or techniques, seen in Asawa’s experimentation with new ways of refining her wire sculptures. From using what she called the “open window” technique, stemming from a mistake that had her cut open an enclosed sculpture and seeing how it curved opened into a new form, she began to work with it. Or her experimentation with acid baths, resulting in new textures and surface effects to her sculptures. From Asawa’s artistic philosophy, we, the viewers, are to determine that there is no direct end, for with experimentation arises new practices of creation.

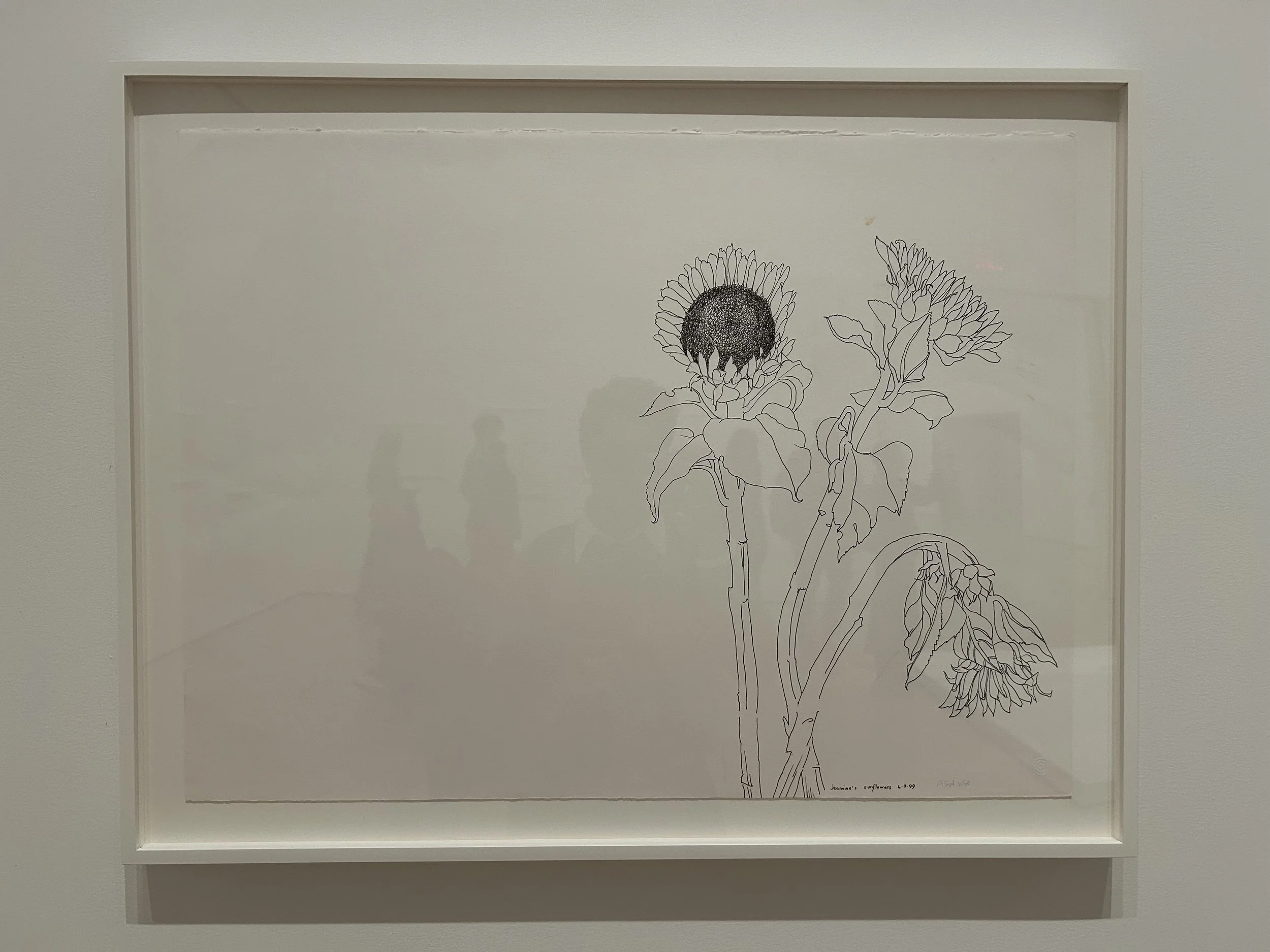

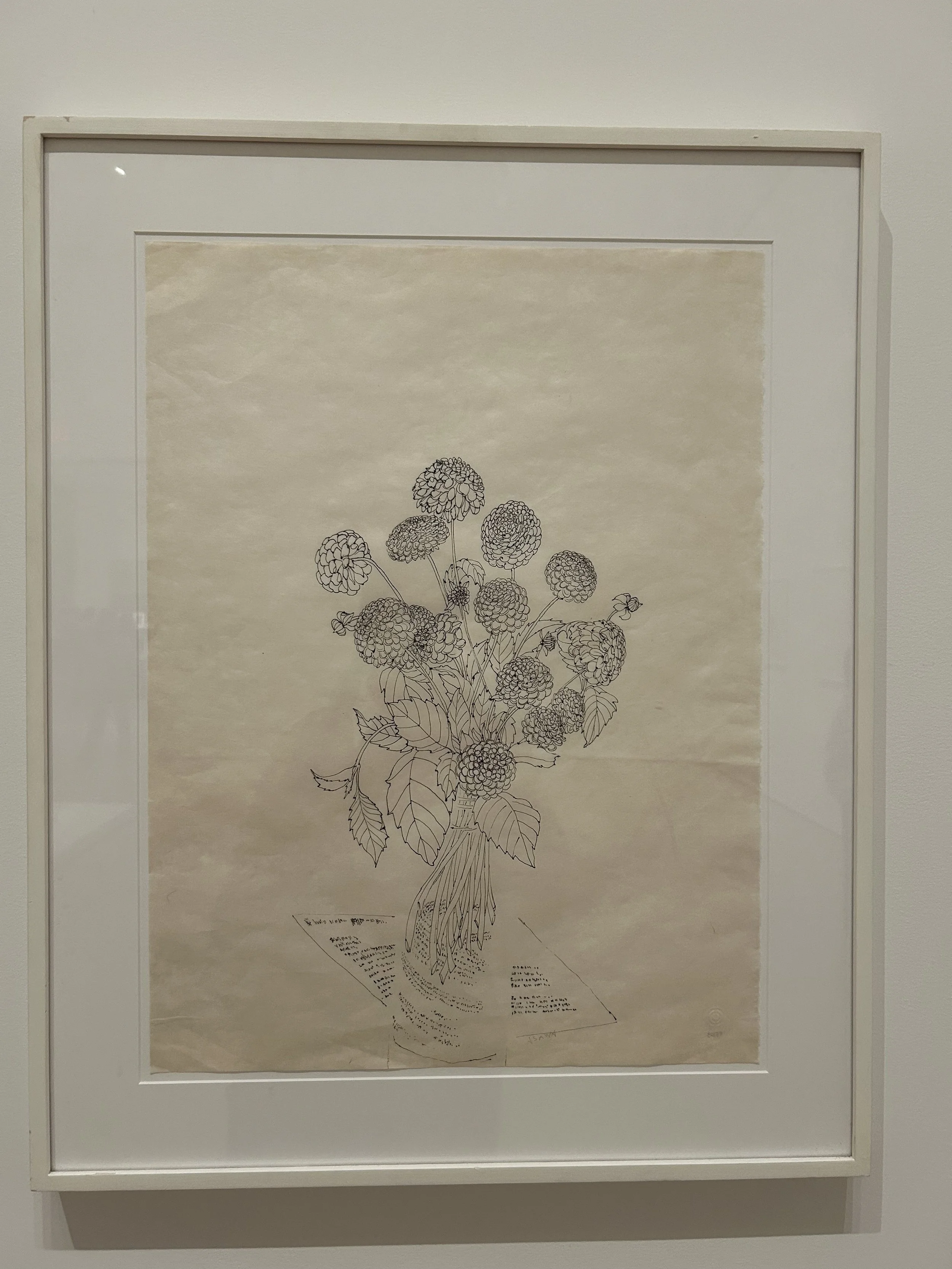

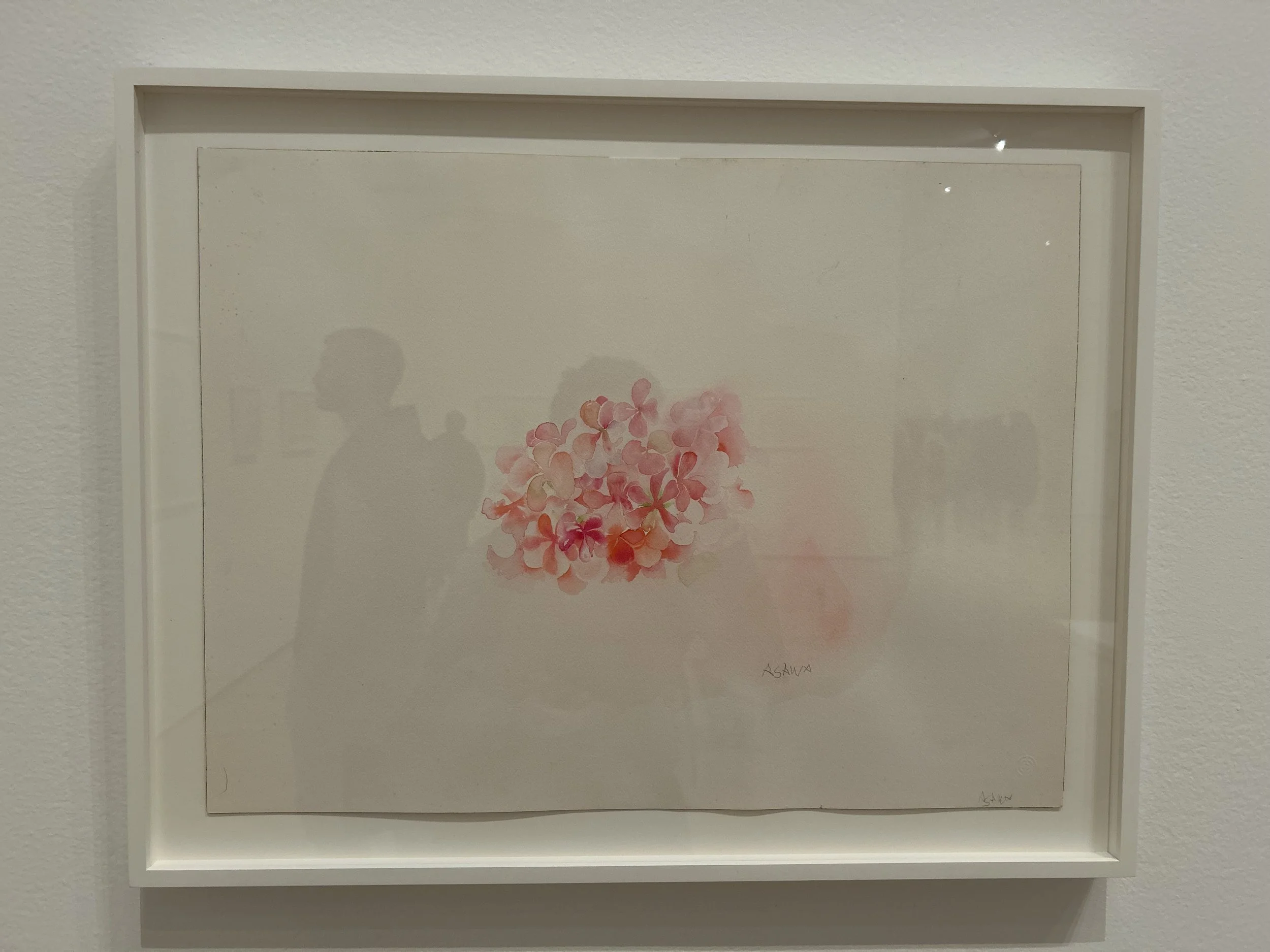

This inspiration from nature continued throughout Asawa’s career and was implemented in the last decades of her career. During this time, her art direction concentrated on observing and rendering flowers and plants. These botanical drawings, ‘life draws,’ as she called them, explored the forms and shapes of irises, hydrangeas, and chrysanthemums, among others, both in realistic and abstract forms. But for Asawa, it was not just drawing from life or rendering an image of what she was seeing; it was also a means of direct interaction with nature. In this way, Asawa learns from nature, but also establishes herself in the present moment and engages not just with herself, but with the world around her.

“There is a prominence even in the flowers themselves. Often gifted by friends and families, as noted in their titles, Asawa not only depicts the physical flowers, but she is marking, in a rendered visual, the history and memory of that individual. Intimately, in this, we see that art making is not just creating, but engaging with the material and with the subject matter at hand. ”

A constant reworking of what can be, followed Asawa through the move to San Francisco in 1949, where she stayed for the remainder of her life. Her constant investigations developed ways of seeing, not just her own immediate world, but in her later works, bringing communities together. Asawa engaged directly with the many around her, expanding her practices to vocalize on education, history, and social advocacy.

The realms the artist reached were in constant growth during the 1950s. Alongside developing a collaging technique with screen-tone, which would later be used by graphic designers and illustrators, under the name of Zip-A-Tone, Asawa also ventured into commercial designing, selling three textile patterns, created by using old techniques of collaging stamp designs, to the furniture company, Englander. Though the company failed to credit her, her design was printed on various products. Through new means of production, Asawa continued to instill her past knowledge and experimentation to produce new languages of art creation and methodology.

![Untitled (SD.201A, Preliminary Drawing for "San Francisco Fountain [PC.004]) 1971 Ink on paper Private collection](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64d6902d80f0e7535c37a81a/1765851024883-US5YD0QTIZPXJ3FTD5DW/IMG_2911.jpeg)

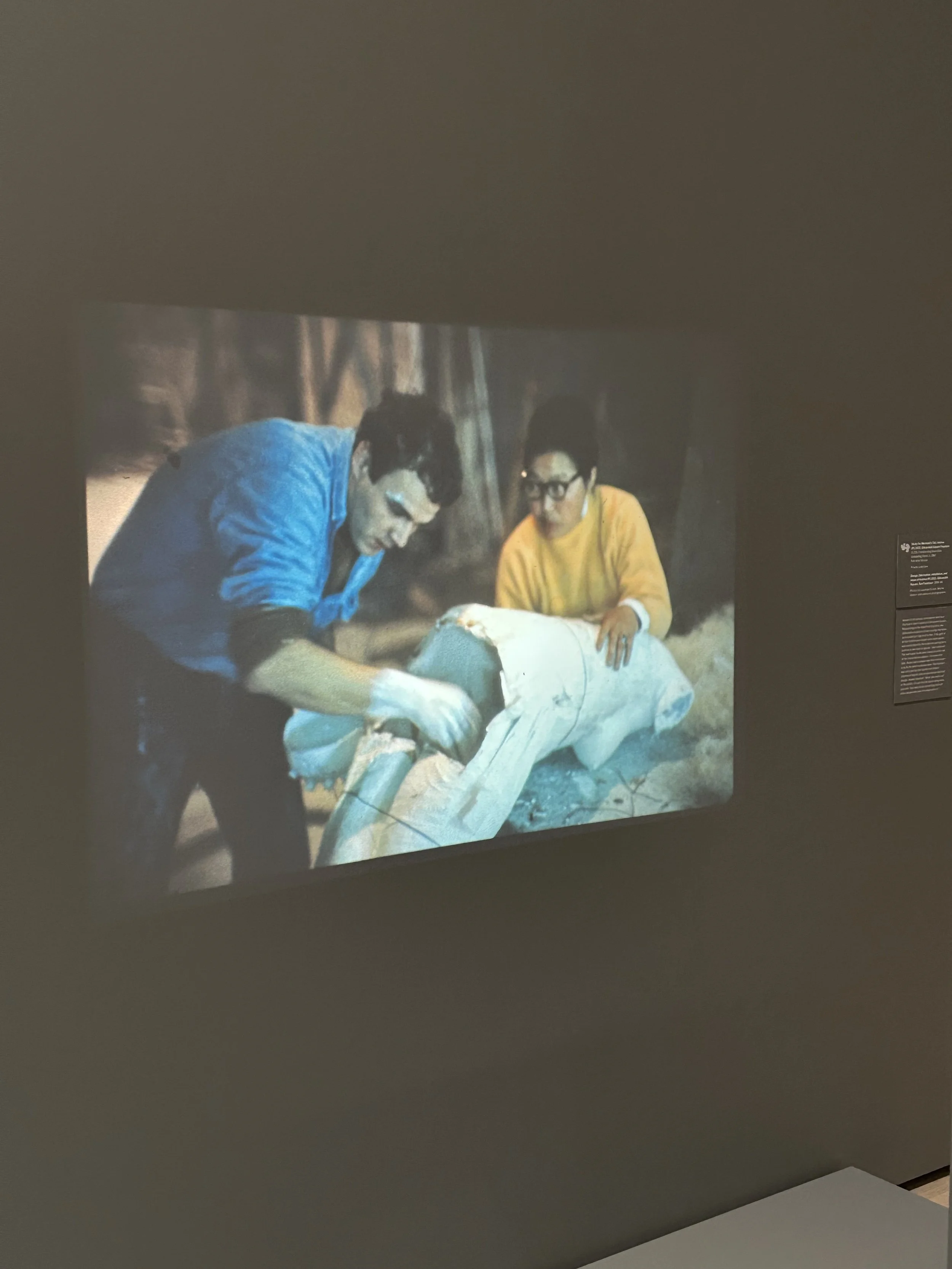

In the late 1960s, Asawa began to teach at her children’s school, using affordable materials as tools for art making. With this hands-on approach to art making in the everyday, Asawa created the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, a group formed by both artists and parents. While this program grew to include dozens of schools across San Francisco, Asawa and the others forged an art practice that was enamored by the usage of both body and mind together, as Asawa states, “using the body and the mind, not separating them.”

In this practice, there was further transformation, as the artist turned the simple mixture of flour, salt, and water into a key material in her relief sculptures. Using the baker’s clay mixture, she cast it in bronze, transfiguring the simple mixture into permanence. Through Asawa’s eyes, all has great potential to form great art. This approach, detailing the grand possibility that can be found in simplicity, is central to Asawa’s artistic practice.

“At the heart of this retrospective, MoMA speaks on the power of art making and the multitude of possibilities that can come from any angle of approach. To Asawa, anyone can create. ”

Asawa’s advocacy towards arts education did not stop in teaching and school programs, but her pursuit to “completing the circle,” as she states, furthered in public commissions of monuments and memorial constructs. Throughout the Bay Area, Asawa’s efforts were ones that held remembrance of the past and lives to be celebrated from the communities around her. Through the hands aiding Asawa in crafting, or sharing their backgrounds and history, the people around the artist were just as important in creating as the materials at her disposal.

From fountains to benches, Asawa’s work brought forth the efforts of many in the community. Through materials used by everyday individuals, and their own efforts, Asawa showcases the power of art making and community, which integrates one and the other, and how it became a pillar for the legacy that she leaves on the art world. Her influence is still felt in inspiring both young and old, showcasing how to see the possibility in creating art. For Asawa, it was important not just to make art, but also to learn from what is created. These creations hold history, and these histories are to be remembered and to be passed on. What is learned is to be passed on.

In Ruth Asawa’s retrospective, we come to learn how to see. We come to learn how to see beyond what is physically visible to us. Sight becomes a sense beyond visibility. It becomes a way to learn and grow. To create and share with ourselves and those around us. In her words, creating art stemmed from everyday tasks. Creativity came from the potential the mundane world brought. “Doing is living,” as she goes on to state. “That is all that matters.” This means of creating came whether sketching her surroundings, or transforming her home into a studio to collaborate with artists and activists. Through taking action and inspiration, Asawa found a means of creating. Through the continuous loops of her wire sculptures, Asawa has taught her viewers how the exploration of art is infinite.

There is no end, nor is there a singular beginning, but simply just doing. This is an act done so through continuous exploration and experimentation, as Asawa has done. And as she has come to show, there is no singular, but only the multitude of possibilities through expanding what is known, into realms of what could be. Even with her self-selected works for an exhibition held between 1954-58, there is a display of growth.

“Through this growth of learned understandings and techniques, one is able to see infinite possibilities at one’s disposal. In changing how we see, we are encouraged to grow.”

Through her work inspiring art, architecture, and designers, Asawa has come to see the world beyond her own parameters, through asking what could be. In taking one simple form of line and shape, Asawa manipulated it into a world of magnitude. Asawa has come to show that what is seen is not a stagnant predisposition. But instead, inspirations and the everyday all around are made up of multitudes; filaments interlocking in ever-changing possibilities. Through Asawa’s work, we learn to see; to see differently what is around us. To see the grandeur in a flower’s petal, and the minute detailing in forged bronze. All of these are convened to see the multitude that are bound, bent, layered, and overlaid to create the story of ourselves.

Published December 18, 2025 | Women in the Arts, Inc. | Images by Osvaldo Martinez Abreu