On the Remnants of “the Home”

In this article, art historian and New York City correspondent Osvaldo Martinez Abreu dissects the defining forms that make up 'the home.' Featuring the works of La Vaughn Belle, and highlights from an interview with Orlando-based artist Tasanee Durrett. This article delves into the Cooper Hewitt Museum's 2025 Design Triennial and investigates the malleable parameters of what can be shaped to form a home. "Making Home" is now on view at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, through August 10, 2025.

To be embraced by walls of memories. Within the traversing hallways of assorted decors of couches, chairs, wooden beams, and blocks of adobe brick laced with names of individuals lost, the 2025 Triennial at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, “Making Home,” is an exhibition content in reconstructing the fragments, known and unknown, that congeal in forming the ideas of what is a home. Within 25 site-specific installations, we are to see the shapes that form and how boundaries are accorded within the definitions of a home. These forms designating notions took form as both physical attributes and emotional convictions; they both acknowledged the physical space, alongside the internal and external connections between the outside world and the internal psyche. Addressing designs of homes between the United States, US Territories, and various Tribal nations, the exhibition goes on to speak on the socially cemented prerogatives of what constitutes a home. This is to be seen as varied and extensive as the very image the word alludes to.

Across its three floors, “Making Home” forges three unifying themes: ‘Going Home,’ followed by ‘Seeking Home,’ and lastly ending on the third floor, ‘Building Home.’ Within the first floor of ‘Going Home,’ we are interlaced within various forms of the domestic home. Spaces rendered in greeting rooms, eating spaces, and living quarters go on to illustrate the varying ways the environment of the home comes to be dignified by interior and exterior spaces. While chronological labeling helps direct to the period one is observing, the key note to explore is the way societal dictations and personal wants come to influence what the home should contain. Individual experiences connected to personal and external history, all influence the design and idea behind the created home.

The second floor, containing ‘Seeking Home,’ unravels the viewers in vignettes of what-ifs. As one comes to explore pragmatic thinking of the reaches of the home, and what it could entail within our time, and beyond, these installations of experiments beckon forth questions of where we have gone, and where we must go. We are to be puzzled and pose questions about the context in which we build spaces that are dignified as home. For many, their allowed reaches are based on systems of power extending from outside forces. Powers accorded greater than the self have historically forced many to leave behind homes and safety. In this they are forced to construct new forms of a home. As such, in this section of the exhibition, one is to address the idea of change, from which come shifting and contorted ideas of newly formed homes. Within these new homes are the echoes of legacy, and what is to be built and what was left behind. In a sense, there is no singular being, but instead, the home is an ever-present and ever-changing form that is kindled in tempered history that harbors the idea of belonging within a physical space, both internally and externally.

The final floor, ‘Building Home,’ takes a reactionary stance. No longer singular in its present, but instead, these assorted models of the home are to be reconfigured as socially constructed actions. It is not just what is to be built, but how to build, and redefining the home for the larger view of the many in communities and cooperative living spaces. In this section, we move from the notions of the individual to address issues of colonization, environmental issues, and historical specificities to render the typologies of building, that which takes into consideration the large-scale perspective of what is needed beyond the individual home. We are to note the impact of history and social constructions beyond the individual home, and we are to embrace alternatives in building to address issues affecting the many.

Harbored among the many forms that the home took within the exhibition, beckoning throughout was the notion of memory. This took shape not solely as a description, but as an actionary form in which “the home” is presented as. Whether old or new, built on the legacy of the past, or forged through own will after relocating and rebuilding, memory takes form as a physical and emotional foundation on which “the home” is built. It is a force that takes no definite shape, but it is always in constant change with new remembrances. It guides and shapes, and remakes notions. It is these notions that give potency to what is called a home. Memory correlating largely to the internal and personal is a factor laced by the outside world of the individual and forces that all too often contribute to how a home expands and takes shape.

“The home” is not just a physical space, but it is in conjunction with a space that memory takes hold of. It beckons questions, where we as individuals are to go and what we have left behind, both good and bad. Factors of the past, present, and potential futures all become defining barriers of what our homes should be, what they should contain, and where their physical parameters should be held. ”

This constant shifting and changing of internal and external factors of memories and what it has taught become central keys in what comes to constitutes a home, where it can be built, what it can contain. Still, they also come to speak, as many have done throughout history and its echoing memories, on the efforts that are needed in building a new home.

The importance of memory is found in its power of remembrance. It is a fuel that kindles means of grappling with the past, whether in a new environment or shifting spaces labeled as ‘home’ to accommodate change. “The home" is present by physical and internal reinforcements that address needs and wants that act upon remembering spaces of the individual, as well as the ecosystem of entire communities. But a harbored truth, cemented throughout the exhibition, is that memory and the idea of “the home” are not a singular, modeled notion. Familiarity with environments comes from realities of social convictions and adjacent history. Within the United States, one must unravel the ideal domestic home and how much it is influenced by racial and social whiteness, and how the permanence of those ideas has left resonances in our present discussions.

“With these truths comes contrasting realities of lived experiences and history that, within the physical and internal bounds of the home, might blind individuals to the truth of neighbors. ”

From what is written as history, one must come to understand that homes and communities are often formed differing from the collective narratives of perceived truths. These can be seen boldly in the memory of Black lives and communities, through the racist policies of the Federal Housing Administration and Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, whose restrictions factored in how these nonwhite communities built and formed homes. These convictions excluded these communities from the collective, and whose memories were labeled as an ‘other.’

But as the frames of memories come to consecrate what can be, it is personal makeups and attractions that become further vistas to which the home becomes a harbor of connecting and reconnecting. These often come within the kaleidoscopic parameters of walls and annotated adornments of the individual. Memory becomes a tool where the roots of what has been and what can be take a cemented hold. Historical changes and social politics all form routes in which the home has to be changed and reshaped by those affected, and their memories live on within the walls inscribed and shaped by them. Recurring through these factors is the connection between past and future, and the influence that the present has on both. Within “Making Home,” memory is to be protected. It is a tool in which the past is catered to and the future is guided towards. Memory of place and time is preserved within the efforts of individuals and communities honing in on the echoes of one’s presence.

In this banquet of bequeathed knowledge and history on Black culture, remembrance, and community, architect and artist Tasanee Durrett states, while interviewed, “the home can be people. It can actually be so many things.” As part of a collective group, Durrett worked with the the Black Artists + Designers Guild (BADG), in redesigning the walls of the ground floor library. In this space, one is to sit and experience Black history and community. From the ground up, BADG, a collective of architects, interior designers, textile artists, furniture makers, and ceramicists, designed and constructed the entirety of the furnished room, from the rugs by one of the founders of the BAD Guild, Malene, to the figurative portrait by Durrett. As a collective, BADG instilled a remembrance of how historical, social, governing, and cultural means have impacted Black individuals and communities. Labeled “The Underground Library: An Archive of Our Truth,” this interactive space of books, art, and artifacts is inspired by the Underground Railroad network that assisted enslaved individuals find freedom in the early 19th century. Installed within the walls of Andrew Carnegie’s library, there is a conversation to have on what it means to house a library, and what that chosen information speaks about the owner. In terms of a library, it is a physical space in which knowledge is stored, protected, and shared, as a means of preservation and regeneration of new ideas. With BADG’s diaspora of Black history and culture settled here, the team of industry creatives, designed a custom space of textile and carpentry as a means of remembrance of the denial of reading that many Black individuals historically have had to face, as well as the abundance of intellectual wealth housed from ancestral homes in the African diaspora, to the present day, that forge spaces of protection against continual erasure. The power of knowledge, and its carrying of truth, functions within this space as a genesis of determining the range of human creation and understanding.

“In these works that act to house history and culture, the library of BADG ‘speaks on educating the public on Black innovation, design, and impact on community,’ as Durrett states. ”

Among written history and objects housing significance on Black culture, sits Durrett’s triptych-like figurative work, “Your Silence Will Not Protect You.” Based in Central Florida, Durrett integrates her architectural background with her practice as a figurative artist, creating mixed-media pieces speaking on the psyche and identity. Through these acts comes the forges of healing among the Black Diaspora. Alongside being a permanent honoree at Women in the Arts Inc, as a past international competition finalist in Orlando, and a United Arts of Central Florida grant recipient, Durrett has exhibited in both group and solo exhibitions, has participated in residencies, most recently a the Art and History Museums, Maitland, with their “Artists in Action” program, and has created public commissioned works and installations, for the City of Orlando, at the Parramore Main Street district, and the Mint Museum, in Charlotte, North Carolina, alongside other awards, honors and recognitions.

Upon a background of bright and umber reds sit two faces detailed in an array of line work, as they stare far into a distance, embraced in pensive thought. Durrett’s work forms a sense of introspection, with its importance, as stated by the artist, “…is to integrate and experience part of a permanence.” Durrett’s work acts as a beacon towards the inward, aiding viewers to encapsulate our internal being and its connection to our place and space in the adjacent physical world. It is a means of introspecting and dissecting the self to reveal our core beings and the vulnerability that comes with practicing these acts.

“To Durrett, there are many masks we wear, whether consciously through purpose, or unconsciously through being circumstances of social and political norms. Durrett asks us to acknowledge these masks and come to a practice of discovering the self and the space that we take up. ”

These spaces, both physical and not, form a language of connection between space and people. With Durrett’s piece, the home becomes a sanctuary space where the masks we all wear can be taken off, and we practice being with an authentic self. To the artist, the home “is a special place, with a feeling of comfort, and where those welcomed in feel cared for.” But in the same way, the exhibition expands the concept of the home from the singular to ideas of the home in a community sense. To Durrett, the home is evolving into a future where the physical boundaries congregate within a community-based living. These spaces do not just form individual personalized safe spaces, but also act as a means of advocating for public spaces to integrate and congregate the many into community groups.

The act of understanding and showing empathy towards others, forms within the act of building a home. For Durrett, a part of the self is integrated within the act of structuring and building. “[The home] is not just a physical space…. There is a higher level of thinking introspectively. It is a unique experience because the home has many layers that relate to all of us.” The home experience is not just the physical parameters of a space to seek shelter, but it is a space of experiences. The very act of Durrett is a personal and intuitive experience. In building, one is tapping from a reservoir of creative ingenuity. But this sense of creativity is integrated from a person, a person of emotion and personal accounts. As Durrett states, “…you can’t be creative without touching the personal.” The individual who builds alongside past experiences and emotions leaves behind part of that within the physical space. This lesson is integrally interwoven within the walls of the exhibition, where one is to reflect on the other. This act of reflecting garners an introspection on the other’s history, culture, and experiences, and how that is maintained within their own space. As a collective, much of Black history and communities are continuously being eradicated. For the artist, defining the home “…means growing and expanding without the erasure. We can grow without compromise.” There is to be constant discovering and rediscovering of what has been built among these communities and understanding its history and legacy as to keep it preserved.

“The more I learn about history and events, the more I feel connected and understand myself.”

In the constant of history and memory holding truths on the built home, as both a physical structure and as a figurative notion in its function of housing, the Cooper Hewitt exhibition does not deterred its viewers from the reality that has gripped many; from Ronald Rael’s installation, “Casa Desenterrada” showcasing the echoes left of 88 victims of indigenous enslavement and the descendants who still live in the Consejos area, to the installation “Birthing in Alabama: Designing Spaces for Reproduction,” a collaboration with obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Yashica Robinson, and architects Lori A. Brown and Trish Cafferky, to illustrate, through vigorous timelines, of the Alabamian system that has historically affected its doctors, nurses, midwifes, and birth-workers from issuing safe and adequate reproductive healthcare. Within art and its creative forms, history is a constant that has been used as a tool to teach in remembrance of what can easily be forgotten by malicious efforts and time.

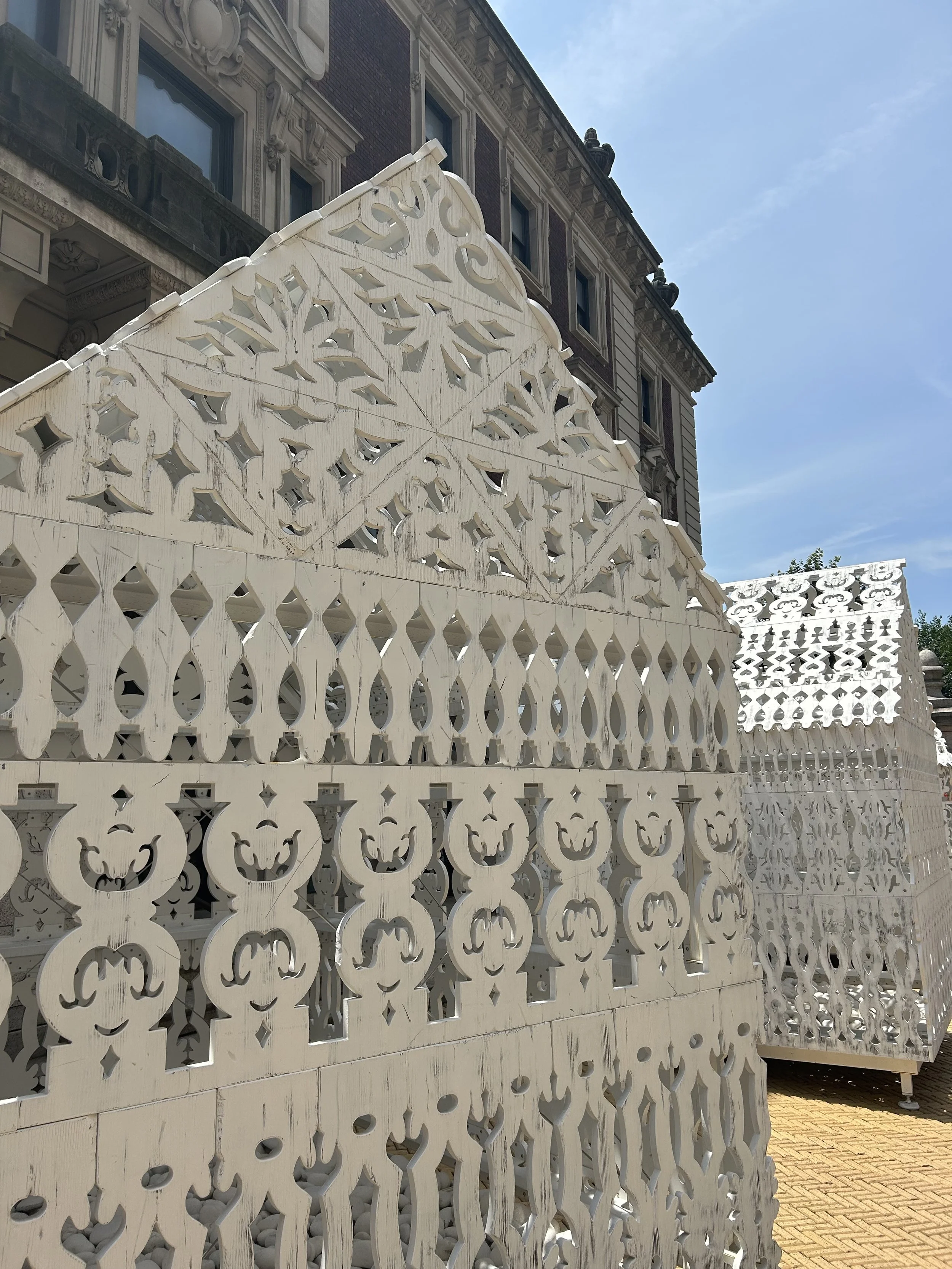

Encompassing visually as wooden framed structures, La Vaughn Belle’s installation, “The House that Freedoms Built,” is a work reverberating from the personal history of the artist. The three structures, welcoming visitors right before the museum’s entrance, are made up of doorless and windowless white wood panels with an interlaced patterned design, known as fretwork, etched throughout, with the floors of the structures paved with smooth white stones. Belle’s multidisciplinary background and work have come to use history as a tool that highlights colonial embedment into the contemporary architectural and material world.

In “The House that Freedoms Built,” viewers are placed within the Caribbean island of Saint Croix. First known as Ay-Ay, before the French renamed it as it is modernly called, the island was colonized within its time under various European rule, 200 hundred years of them under Denmark, until it was sold to the US in 1916.

“The influence of its European rule would persist to the present, through the architecture popularized by the French, who built the first long-lasting structures, and the Danish, who would later rule and rename towns and cities after their royalty. But alongside its waterfronts, the reality of history still lingers, though the auction houses that once held enslaved individuals and whipping posts have been taken down from public view. ”

In its outward appearance, the three installations are reminiscent of 18th-century structures that were inhabited by formerly enslaved individuals. These individuals fought for their freedom and were allowed to settle in Christiansted, Saint Croix. The embellished design of the fretwork is meant to illustrate architectural details found in homes in the town of Frederiksted. The town was home to a labor revolt in 1878, known as the Fireburn, where laborers revolted against working conditions and burned down a third of the town and over fifty plantations. In the aftermath of reconstruction, many designs for homes continued the usage of the fretwork design.

Through the architecture and history of Saint Croix, Belle’s effort comes to highlight the colonial and enslavement that is built within the island, as well as the complex legacy in the contemporary period that still harbors its echoes. Throughout her exhibitions across the Caribbean, the US, and Europe, Belle centers her work on making seen what can quickly be forgotten. History so often is handled by those in power to write what is beneficial for them, and often it is Black and communities of color who are erased, forgotten, and taken out of history; an issue that is ongoing and kindling in our contemporary time.

“While the architectural structure encompasses a physical space, in the same vein as Durrett highlights the importance of the self in building, Belle speaks upon the history that is interlaced by built material culture and structures. Sometimes in fragmented remnants, Belle focuses on cementing truth and visibility into the narratives of those silenced by colonial history.”

As in her birthplace of Trinidad in Tobago, an island that has been under seven different colonial rules, the reverberating imprints of colonial impact are felt personally and globally. Not just to learn and understand, but to experience the history of many that have come before, and their descendants in the present.

![Terrol Dew Johnson (1971–2024, Sells, Arizona [Tohono O’odham Nation]; active Sells, Arizona) and Aranda\Lasch (Established 2003, New York, New York; active Tucson, Arizona, and Brooklyn, New York), Installation of “We:sic 'em ki: (Everybody’s Home)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64d6902d80f0e7535c37a81a/1753798901736-CPXE9P24V923QUYXWPX4/IMG_1633.jpeg)

Belle’s work whispers onto the notion that history and memory are not just intangible things, but are spaces that can be inhabited. Space under the title of ‘home’ is not a construct solely defined by a means of a seen physicality. We, as people of history and memory, are in a constant state of living within the construction of these concepts. Whether we consciously acknowledge them or not, they are forces that harbor truth in their power to temper. Emblems left by history come to detailed understandings of our present, and where our futures are being built. In Belle’s structures holding imprints of the effects of colonialism, she holds tightly the pertinence of knowing the individual and their history. These spaces are walls of memories. They are not solely structures to shelter the needs of an individual, but the exhibition as a whole, seen through the works such as of Belle and Durrett, gives means of highlighting how they are wells of nurturing knowledge, history, and memory. The emblems of the home are not just in the physical bounds one comes to forge their space. The structure, whether a physical space or not, is forged through the individual. Individuals themselves are structures of emotions, cemented by memories of the past and present. Homes that physically encompass a space are framed by those emotions and memories. They reflect past and history, alongside current states of the self and its connection to the world around it. They reflect and shift in kaleidoscopic means what it is to be. There are no means of straightforward answers to what it entails to ‘make a home.’ As varied and ever changing as its descriptive word comes to detail, ‘the home’ is a living state and being. Its structure, within states of physical and incorporeal being, conserves the power of knowledge and truth. From these segments comes a form of understanding, both towards the self and towards others.

Published July 31, 2025 | Women in the Arts, Inc. | Images by Osvaldo Martinez Abreu or otherwise noted.